Combatting sudden cardiac arrest in runners, one step at a time

Although rare in runners, sudden cardiac arrest is often fatal. But what is being done to prevent it?

All Richard Moore remembers was feeling relaxed.

It was 2022, and he was 400 metres from the finish line of the renowned Blackpool Marathon.

The next thing he knew, he’d woken up in hospital — six or seven hours later.

“I initially thought I’d been hit by a car or I’d fallen over the seawall, every kind of incident that may have happened rather than I’ve had a heart attack,” he said.

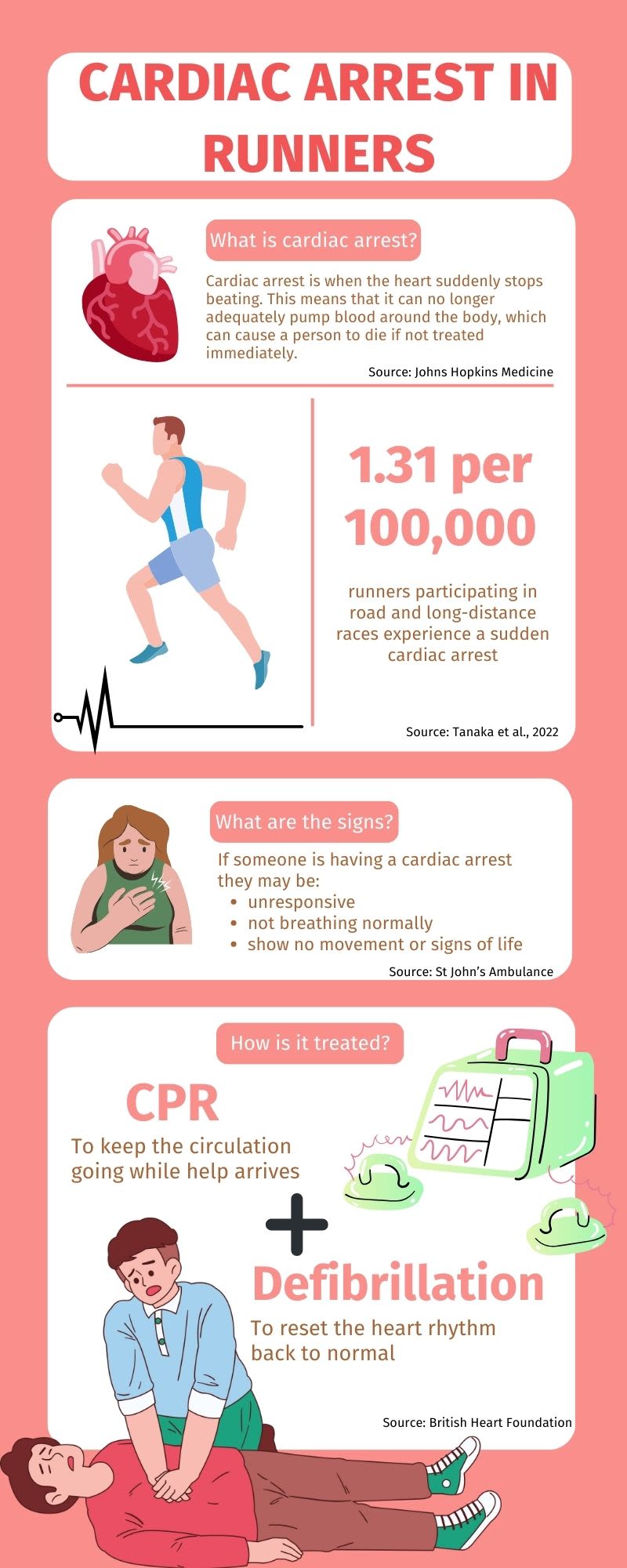

What Moore — a self-employed graphic designer from Southport — had experienced was a sudden cardiac arrest, when the heart abruptly and unexpectedly stops beating. This means that blood is no longer being pumped around the body, including to the brain. If left untreated, death can ensue in minutes.

Moore was one of the lucky ones.

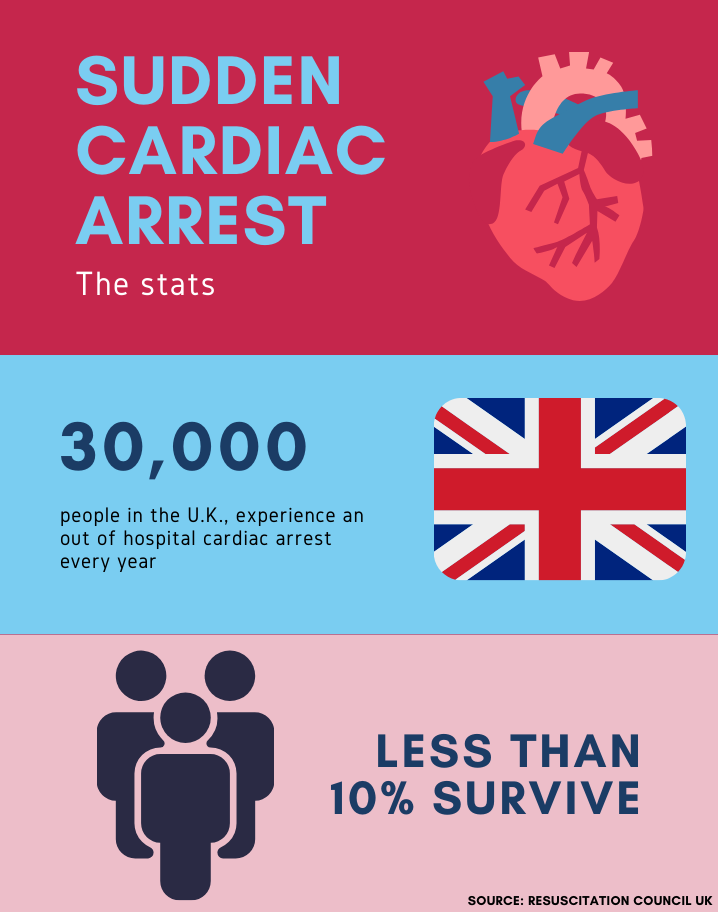

Every year in the UK, around 30,000 people experience an out of hospital cardiac arrest, of which less than 10% survive.

Cardiac arrest can happen to anyone at any time, but it’s often athletes like runners who make the headlines.

In 2016, war veteran David Seath, 31, tragically lost his life due to a suspected cardiac arrest during the final stretches of the London Marathon. Three years later, 35-year-old Nicholas Beckley suffered a fatal cardiac arrest after the Cardiff Half Marathon and just last year, a 21-year-old runner in Spain collapsed while crossing the finishing line of a half-marathon, later dying in hospital. Again, of a cardiac arrest.

Despite the headlines, cardiac arrests in long-distance runners are rare. The most recent data suggests 1.31 per 100,000 runners participating in road and long-distance races experienced a sudden cardiac arrest.

Although rare, every death is a tragedy. So what is being done to reduce them?

Preparing for race day

GP trainee Dr. Amy Boalch has been working in the medical teams at marathons for the past few years. She and her colleagues noticed that while running has become an increasingly popular pastime, appropriate and user-friendly medical information was often not easily available to participants. So, they decided to create an app called Race Ready which runners can now download.

The idea is to provide evidence-based medical advice to runners, covering everything from blisters to sudden cardiac arrest. That way, they can be better informed about what is going on in their bodies, both in training, and on race day.

“If anyone’s having exercise-associated symptoms that include chest pain, dizziness, feeling faint, or they’ve had a family history of sudden cardiac death, that means that they need to stop exercising and see a doctor urgently,” she said.

Large events like the London Marathon will have medical expertise on site to deal with any potential cardiac arrests. Yet, no matter how much medical support is available, bystanders are often going to get there fastest, Dr. Boalch said. And that is where the importance of learning basic CPR comes in.

A coffee break to save a life

Learning CPR and being comfortable with using a defibrillator is one of the most important things you can do, said Imogen Beresford-Bone, who has been volunteering with the Medical Response Team at St John Ambulance (SJA) for about five years. It’s this team’s job to extract vulnerable patients from crowds, such as those seen at big running events, and take them to a safe place where they can be properly assessed.

Over the years, Beresford-Bone has seen three sudden cardiac arrests, and was one of the team who helped save the life of Dr. Ian Quigley in 2021, who suffered a cardiac arrest at the finish line of the Royal Parks Half Marathon.

SJA provides a range of appropriate resources on their website that can be consumed in a coffee break, she said.

“We’ve got resources there that will tell you how to recognise someone in cardiac arrest, how to use a defibrillator and how to give CPR,” she said.

What may be five to ten minutes of learning may mean that “tomorrow, next week or even in a year’s time, you could give someone a lifetime back,” she said.

Beyond being able to use a defibrillator, people need access to them in the first place. That’s why Moore set up a charity called The Southport Saviours Foundation which campaigns for accessible 24/7 defibrillators in the community.

Defibrillation, which aims to reset the rhythm of the heart, can be lifesaving. When used within three to five minutes of collapse, it can improve survival rates by up to 70%.

Moore’s charity is trying to get the conversation started around defibrillator access, helping to install them, for instance at running clubs and outside shops, as well as providing vital first aid training.

“We’re the last line of defence really, catching people at the very end,” he said.

Detecting a silent killer

Genetic screening is another potential tool to protect runners.

In a 2012 study of millions of runners participating in marathon and half marathon events in the US, cardiovascular disease accounted for most cardiac arrests. In particular, the leading cause of death in participants was a condition called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. This is when the muscular walls of the heart thicken and become stiff to the point where it’s harder to pump blood around the body.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is usually hereditary and is thought to affect one in 500 people in the UK. Unfortunately, many people don’t realize they have it, which can partly explain why young, active and otherwise healthy individuals can, in rare circumstances, suffer a cardiac arrest seemingly out of the blue.

“In most cases of sudden cardiac arrest or death there’s some degree of underlying cardiovascular disease,” said Jamie Edwards, a cardiovascular physiologist at the University of East London.

“The younger the athlete it happens to typically the more likely it is a congenital abnormality, something that they were probably born with that wasn’t identified.”

“In most cases of sudden cardiac arrest or death there’s some degree of underlying cardiovascular disease”

- Jamie Edwards, University of East London-

Athletics isn’t the only sport impacted: In 2004, Hungarian footballer Miklós Fehér died during a match from a sudden cardiac arrest that was caused by hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A year earlier, Cameroonian footballer Marc-Vivien Foé suffered the same fate.

There’s currently no routine national screening policy for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the UK. However, genetic tests may be offered on the NHS for people who have a family history of sudden cardiac death, according to the British Heart Foundation. The charity Cardiac Risk in the Young also subsidises screening for young people aged 14 to 35.

Advice for runners

Despite these precautions, the risk of sudden cardiac arrest cannot be completely avoided. Yet for those who may be concerned, it’s important to not forget the overall health benefits of running.

“The benefits in terms of reducing disease, improving quality of life, extending life are huge and far outweigh the risk of having a heart attack or your heart stopping during exercise,” said Charles Pedlar, a professor of applied sports and exercise science at St Mary’s University in Twickenham.

As for Moore, he was soon back in his stride and distance running within a year. Now, when he heads out for a run, he makes sure to take his phone so that he can call for help, both for himself or anyone else he encounters.

His advice for fellow runners?

“Listen to your body,” he said.

“Nobody knows your body better than you.”